(đã được dịch ra Anh và Pháp ngữ)

Ðã có một thời như thế….

Trong cái đám đông ồn ào ấy, người thiếu nữ cũng chen vào. Nàng hơi choáng váng vì mùi xú uế của đống rác gần đó xộc lên. Nó gợi cho nàng cái cơn buồn nôn chờn vờn mãi từ ngày hôm qua chưa chấm dứt, mặc dầu nàng đã nén nó xuống từ nãy bằng một viên kẹo bột.

Vị đường ngọt lịm vẫm còn dính đâu đó ở kẽ răng, nhưng viên kẹo thì đã tan hết. Nàng có thể cất giọng nói to mà không bị bướng víu cái gì ở trong miệng.Trước hết nàng cất tiếng chào một bà cụ ngồi bán thuốc lá cuộn, bó thành từng bó, bày trên chiếc mẹt ở ngay mé vỉa hè. Bà cụ đáp lại bằng những tiếng gì nghe không rõ vì đám đông ồn quá. Bên tai thiếu nữ, nàng chỉ nghe thấy những tiếng chào mời om xòm của mấy người đứng bên cạnh, và nhất là tiếng cười nói tục tĩu vang lại từ mấy thanh niên ở gần đó. Trên tay của họ là những xấp quần tây dài. Ðủ loại vải. Ðủ loại màu. Nhiều nhất là màu ka-ki bộ đội. Có anh cầm trên tay tới ba, bốn cái, bên tay kia còn giơ cao thêm một cái nữa. Một vài người đi qua, đứng lại ngắm nghía, lật bên này, giở bên kia, xem cho có rồi bỏ đi. Từ sáng, chưa thấy ai bán được món nào, mặc dầu tất cả đã phải bỏ chạy ba bốn lần vì công an kiểm soát chợ đi rảo nhiều lần.

Ðây là khu đất hẹp ngay đàng sau lưng của chợ Ðồng Xuân, một vùng đất hạn hẹp, phụ thuộc nhưng đầy vẻ mâu thuẫn so với cả một khu vực đã đi vào nền nếp từ bao nhiêu năm nay. Nhưng cũng chính vì tính chất phụ thuộc ấy mà nó trở nên hỗn độn, phức tạp hơn nhiều so với cái quang cảnh vắng hoe ở ngay trong lồng chợ. Vào trong đó thì cái gì cũng sạch, cái gì cũng ngăn nắp, chỉ phải mỗi tội là hầu hết đều phải mua bằng tem phiếu. Nhiều món hấp dẫn khác lại chỉ được bày cho có, với mảnh giấy ghi rõ là “hàng mẫu”. Như thế chẳng trách gì nhân viên phục vụ đông đảo hơn khách mua hàng.

Rút cục, chẳng cần xua đuổi, mọi người cũng đã tự động rút ra sinh hoạt ở mé ngoài, tạo thành một xã hội bên lề của xã hội. Tất cả đều lam lũ như nhau, cùng chen lấn, hỗn độn, chìm ngập trong những mớ gồng gánh, thúng mủng giăng la liệt ở khắp các lối đi. Vào những hôm mưa, con đường trở nên lầy bùn, dẫm chân lên thấy lép nhép. Rác rưởi quăng bừa bãi, người chen nhau trên từng khoảng đất nhỏ vừa đủ để đặt chân tới.Thỉnh thoảng gặp một cái xe đạp thồ nghênh ngang đi vào thì cả đám đông đều bị nghẽn ứ lại. Tiếng chửi rủa cất lên. Tiếng cãi lại còn to giọng hơn nữa. Ðủ loại danh từ tục tằn được văng ra. Không nói được ở cơ quan, không văng được ở các buổi hội họp, không được phát biểu tự do cho nó đã cái miệng, thì sự dồn nén ấy được sì ra hết ở đây.

Bọn thanh niên phải kể là đã văng tục nhiều nhất. Từ nãy đến giờ, người thiếu nữ đã nghe đến hàng chục lần câu nói tục tĩu từ anh chàng trai trẻ đứng ở chỗ gần nàng nhất. Nàng không bực mình vì những từ ngữ hắn dùng, nhưng cái tội của hắn là đã la to quá. Tiếng nói của hắn xoáy vào màng tai của nàng nghe như những tiếng búa đập lên đe, vừa gọn vừa sắc. Nó làm cho cơn khó chịu của nàng tăng lên và lại bắt đầu thấy lợm giọng. Nàng định móc túi lấy thêm ra một viên kẹo nữa thì sực nhớ đến nhiệm vụ của mình. Nàng bỏ ý nghĩ lấy kẹo ra ăn và giơ cao chiếc áo đang cầm trên tay, cất giọng chào mời một đám khách hàng vừa đi qua đó.

Cái áo gây được sự chú ý của mọi người. Nó là một cái áo tây bằng vải ka-ki màu vàng, đã cũ rích cũ mèm, nhưng chính vì nó quá xưa cũ mà cái kiểu áo còn mang một vẻ rất “tây”. Tay áo dài và rộng, ráp lên hai bờ vai thật khéo không một vết nhăn nhúm. Cái kiểu cổ bẻ, hở xuống tới ngực rồi chạy tiếp hai hàng nút áo, mỗi bên có ba chiếc khuy bằng đồng chạm trổ, đem lại một vẻ phong lưu mà xuất xứ của nó, hẳn phải là của một tay chơi sành từ hai ba chục năm về trước. Tuy lâu đời là vậy, nhưng là vải hàng ngoại, lại được giữ gìn, nên mặt áo trông vẫn còn tươm. Thiếu nữ giơ cao cái áo lên quá đầu của mình.

Nàng nói với một người đang đi tới:

“Áo này mặc vừa, mua đi anh giai!”

Người khách ngừng lại, nhìn hững hờ. Biết anh ta chỉ tò mò thôi, nhưng nàng vẫn nói thêm:

“Ba chục thôi, mùa đông này mặc ra ngoài áo len, ấm phải biết.”

Người khách toan thò tay ra ướm, bỗng nghe thấy cái giá “ba chục” bèn rút ngay lại. Ông ta nhìn thiếu nữ với ánh mắt cười cười. Thiếu nữ cảm thông ngay rằng, những hạng như của này thì chỉ nên mua cái đồ giẻ rách đáng giá ba đồng.

Rồi một đợt khách nữa đi qua, thiếu nữ lại mời chào. Sự đón đợi của nàng cứ giảm dần đi. Nàng bắt đầu trở lại cái cảm giác khó chịu như buồn nôn vẫn chờn vờn ở cổ. Nàng thò tayvào túi nhón một viên kẹo bột khác bỏ vào miệng. Bây giờ nàng thì khám phá ra cái nguồn gốc của cơn khó chịu này vốn đã ám ảnh nàng từ suố ngày hôm qua. Nó không phải vì nàng đã ăn bát mì vữa mà đứa em của nàng bỏ đó từ chiều hôm trước. Nó cũng không phải vì nàng đã nhiễm lạnh sau khi phơi mình giữa làn sương đêm. Nàng nhớ ra rằng, trong lúc sử dụng cây cuốc, nàng đã cuốc nhằm giữa lưng một con cóc. Con vật không kịp kêu lên một tiếng thì đã bị dẹp lép sau một tiếng “bụp” khô khan. Nàng có cảm giác như những mảnh xương gẫy của nó truyền được cái âm thanh khô khan đó dồn qua cán cuốc để vào được đôi bàn tay chai cứng của mình. Từ cái phút ấy nàng bắt đầu thấy rờn rợn ở trong đầu, rồi càng nghĩ tới nàng càng cảm thấy lợm giọng thêm. Con cóc là một sự sống. Chính nàng đã đập giập sự sống ấy để biến nó thành một đống bầy nhầy.

Bây giờ cơn ám ảnh đó vẫn còn, và còn gia tăng hơn nữa vì cái mùi xú uế bốc lên từ những đống rác ở ven chợ. Nàng lại lợm giọng, và nàng thèm được ọe ra một lần cho nó nhẹ nhõm trong người, mặc dù từ sáng, nàng chưa ăn gì ngoài mấy viên kẹo bột.

Vừa đúng lúc nàng vắt cái áo tây vàng lên vai định rời chợ thì có một người khách ngừng lại ở ngay trước mặt. Không phải là một người đàn ông, mà lại là một người đàn bà. Bà ta ngó sững cái áo tây vàng như bị thu hút bởi một sức lực kỳ lạ, rồi thiếu nữ thấy mặt của bà hơi tái đi. Bà ta xòe tay ra nắm lấy cái áo trong khi hai mắt của bà bỗng nhìn xoáy vào mắt thiếu nữ bằng những tia dữ dội. Nàng không ưa cái cung cách có ai nhìn thẳng vào mắt mình như thế. Nàng càng không ưa cái vẻ mặt xanh tái với nước da màu chì trên khuôn mặt dữ dằn của thiếu phụ đứng trước.

Bà ta trạc khoảng năm mươi, nhưng nếu nhìn thật kỹ để thấy cái nét tươi trẻ phảng phất ở vành môi và vầng trán phẳng thì tuổi của bà chỉ đến bốn mươi là cùng. Thiếu nữ cố gợi lại trong óc của mình để tìm xem bà ta có gì liên hệ đến mình, nhưng trong một vài giây ngắn ngủi, nàng chỉ thấy như mình bị xao động bởi cái nhìn của người đối diện, với đôi mắt đục lờ hơi sếch lên, ẩn dưới đôi lông mày khá đậm.

Bây giờ thì người đàn bà đã gỡ được cái áo trên tay của thiếu nữ. Bà ta rũ tung nó ra và giơ áo lên bằng cả hai tay. Thiếu nữ có cảm giác ngay rằng bà ta không xem xét như thể để hỏi mua. Nàng muốn giằng cái áo lại để lui đi, nhưng người đàn bà đã nắm chắc lấy nó bằng hai bàn tay xương xẩu, đầy gân xanh của mình. Bà ta cất giọng hỏi hách dịch:

“Cô lấy cái áo này ở đâu?”

Thiếu nữ thấy lành lạnh ở sống lưng. Nàng ngó sững lại người đàn bà. Vẻ hung hăng của bà ta đem lại cho nàng một thoáng bối rối. Nhưng rồi nàng đã biết mình phải làm gì cho qua cơn xui xẻo này. Nàng đáp bằng giọng thản nhiên:

“Tôi mua đi bán lại!”

Vừa nói, thiếu nữ vừa xông tới, giật cái áo ở trên tay người đàn bà. Nàng hoàn toàn thất bại trong công việc đó và chẳng những nàng không cầm được chiếc áo trên tay mà còn bị người đàn bà túm ngay lấy cánh tay của mình nữa. Thiếu nữ cảm thấy những móng sắc của bà ta bấu cứng lấy da thịt mình. Ngay khi đó thì nàng biết mình vừa làm một chuyện sai lầm. Nàng đã tiếc cái áo một cách dại dột nên thay vì bỏ chạy đi, nàng đã xông tới.

Bây giờ thì đã quá muộn. Thiếu phụ đã đeo cứng lấy nàng bằng những móng vuốt của bà ta. Nàng có cảm giác như bà ta đã chất chứa bên trong tấm thân gầy gò ấy một sức khỏe lạ lùng. Nàng đã thử vùng lên chạy, nhưng những móng sắc càng bám sâu thêm vào làn da, làm thiếu nữ đau đớn. Nàng hơi nhăn mặt, và cất giọng cau có:

“Ô hay! Làm cái gì thế này?”

Người đàn bà tác sác:

“Tao hỏi mày, mày lấy cáo áo này ở đâu ra?”

“Tôi mua đi bán lại!”

“Ðồ điêu! Mày ra công an với tao, xem mày còn điêu ngoa được như thế mãi hay không?”

Thiếu nữ giằng lại. Bà ta lôi đi. Cuộc giằng co làm náo loạn cả một góc chợ. Mọi người xúm lại. Có cả trăm câu hỏi cùng một lúc nhao nhao lên:

“Ăn cắp hả?”

“Ăn cắp hả?”

“Ðánh bỏ mẹ nó đi. Không chịu lao động, chỉ ngồi không ăn bám!”

Sự ồn ào ấy trong khoảnh khắc đã thu hút mấy đồng chí an ninh ở quanh chợ. Một người xông tới, phụ với người đàn bà giữ cứng thêm một cánh tay nữa của thiếu nữ. Tóc của nàng bây giờ xổ tung. Hai chiếc khuy áo trên ngực cũng bị banh ra. Nhưng thiếu nữ không nhìn thấy gì, không phân biệt được gì trước khung cảnh hỗn độn ồn ào trước mắt. Nàng nghĩ đến hai em đang còn ở nhà. Nàng nghĩ đến cặp mắt dữ dội của thiếu phụ. Nàng nghĩ đến cái áo tây vàng và hình ảnh của con cóc dẹp lép bầy nhầy. Tất cả ùa đến thật nhanh, choáng ngộp hết đầu óc nàng và nàng để mặc cho mọi người lôi mình đi như lôi một con vật.

Tới đồn công an, người đàn bà trung niên khai rành rọt:

“Thưa các đồng chí, tôi vừa chôn chồng được đúng năm ngày.Tất cả giấy tờ khai báo, thủ tục tôi còn giữ đầy đủ cả ở đây. Trong lúc khâm liệm cho chồng, tôi có để cho ông ấy một chiếc áo tây vàng. Chiếc áo này đây. Nó quen thuộc với gia đình tôi từ mấy chục năm nay. Tôi có thể chỉ ra rất nhiều dấu vết mà tôi đã thuộc nằm lòng. Vậy mà hôm nay đi chợ, tôi thấy cô này đứng bán đúng cái áo đã chôn theo chồng tôi. Nhờ các đồng chí điều tra hộ, cái áo ở đâu ra? Làm sao cô ta có được cái áo đó?”

Tất cả mọi người trong phòng đều sửng sốt. Mấy đồng chí công tác ở bàn kế bên cũng bỏ cả việc, mở to mắt ra nhìn. Trong cả trăm ngàn vụ rắc rối về đời sống ở đây, chưa bao giờ lại có chuyện xảy ra lạ lùng đến thế. Mọi con mắt đều dồn về phía thiếu nữ. Nàng có vẻ còn mệt mỏi sau một cuộc lôi kéo ồn ào giữa đám đông, nhưng bây giờ nàng đã lấy lại được vẻ bình thản hằng ngày, và nói cho đúng hơn, thật khó có thể đoán ra được tâm trạng của nàng sau vẻ mặt lầm lì và ánh mắt sắc sảo lạnh lùng. Nàng đã biểu lộ một thái độ không nao núng, mà cũng chẳng sợ hãi, đúng là một thái độ của một kẻ đã bị dồn đến đường cùng và sẵn sàng đương đầu với tất cả.

Chính thái độ ấy đã khiến cho anh chàng công an trẻ, mới khởi đầu giở giọng nạt nộ nhưng rồi sau cũng phải dịu xuống. Nàng không để cho ai mắng mỏ mình. Với thiếu phụ trung niên, nàng nói:

“Ờ thì cái áo ấy của ông chồng bà. Bà không cần phải la lối om xòm.”

Thiếu phụ cũng chỉ cần nàng xác nhận có thế. Bà ta giơ hai tay ra trước mặt, về phía đám công an lố nhố ở trong phòng như để phân vua: “Thế đấy! Thế đấy! Tôi có vu oan giá họa cho ai!”

Rồi bà ta ngồi xuống ghế, thở dốc. Sau một hồi cố gắng, kể từ lúc túm đứa con gái to gan này ở ngoài chợ cho đến lúc nó phải xác nhận rằng cái áo tây đó là của bà, bà ta đã hoàn toàn đạt được những thắng lợi mà mình mong muốn. Sau đó là phần của nhà nước. Nhà nước sẽ xử lý vụ này, sẽ phải làm cho ra nhẽ. Nếu cần, bà sẽ thưa lên tới thành ủy. Nhưng sự sốt sắng của các đồng chí công an trong vụ này làm bà hài lòng. Bà thấy mình nên đóng vai trò hiền lành, chân chỉ thì sẽ có lợi hơn, vì đằng nào sự thể cũng đã hai năm rõ mười. Nghĩ như thế bà dịu hẳn vẻ mặt của mình xuống và chẳng mấy chốc, mọi người nghe thấy tiếng của bà ta khóc sụt sịt. Bàn tay của bà quơ lấy dải khăn tang dài lên lau mặt một cách cố ý để cho mọi người nhìn thấy.

Ðiều này có kết quả ngay vì đồng chí công an ngồi ở bàn giấy giữa đã an ủi bà bằng một giọng dịu dàng rồi quay qua thiếu nữ, cất giọng nạt nộ:

“Biết điều thì khai hết đi, nếu không thì tù mọt gông!”

Thiếu nữ hơi nhếch cặp mắt lên, ánh mắt vẫn đầy vẻ lạnh lẽo, và nàng cất tiếng hỏi lại:

“Chế độ ta cũng còn có “gông” hả đồng chí?”

Bị hỏi móc họng, đồng chí công an tái ngay mặt lại rồi sau đó vụt đỏ bừng lên. Ðồng chí ấy tác sác để xí xóa câu nói hớ hênh của mình:

“Ðừng có đánh trống lảng. Cái áo mày lấy ở đâu. Khai ra đi!”

“Việc gì tôi phải đánh trống lảng. Việc gì tôi phải chối cãi. Nhưng tôi yêu cầu đồng chí bỏ cái giọng “mày tao” ấy đi. Tôi là nhân dân. Ðồng chí phục vụ nhân dân, đồng chí không có quyền nói năng với tôi như thế.”

Bị hai đòn phủ đầu liên tiếp, anh chàng công an đột nhiên sững sờ hẳn lại. Anh ta nhìn người con gái ngồi ngay trước mặt với một vẻ vừa ngạc nhiên, vừa tò mò. Kinh nghiệm cho thấy những loại cứng cỏi như thế hẳn gốc gác của nó phải có gì đáng gờm. Vậy thì không ai dại gì mà húc bừa vào những “của” mà tông tích chưa rõ ràng. Thế là anh ta nhỉnh ngay nét mặt, và xuống giọng ôn hòa:

“Ðược rồi! Tôi rút lại cách xưng hô đó. Nhưng tôi nói trước cho cô biết, muốn xưng hô cách nào thì xưng hô, cô phải khai cho hết. Cái áo đó cô lấy ở đâu?”

Thiếu nữ buông sõng một câu:

“Ðào mả!”

Giọng nói của nàng sắc, gọn, lạnh lùng, thản nhiên, không một chút xúc động. Ðiều đó làm cho mọi người cùng sửng sốt lên một lượt. Ðến ngay thiếu phụ đang ngồi sụt sùi cũng vội ngưng ngay tiếng khóc để giương to mắt lên nhìn.

Ðào mả thì dĩ nhiên rồi, nhưng bà ta không thể tin được rằng câu chuyện động trời ấy lại được thực hiện bằng chính ngay thiếu nữ mảnh mai ngồi ở phía trước mặt. Bà ta chợt nhớ đến hành động của mình trong vòng nửa giờ trước đó. Giât lấy cái áo trong tay nó rồi túm nó ở giữa chợ. Ðiều nó đi qua một dẫy phố để tới đồn công an. Vậy mà quân trời đánh thánh vật này không xỉa cho bà một dao thì quả là bà vừa thoát khỏi một tai nạn tầy trời. Nghĩ như thế, bà ta thấy rúm người lại, nếu ở quanh đó không đầy rẫy những bóng dáng công an áo vàng thì bà ta đã vùng lên, bỏ chạy đi rồi.

Bây giờ thì bầu không khí trong phòng có vẻ nghiêm trang hơn lên. Ðây không còn là một vụ ăn cắp, ăn trộm hay mua đi bán lại nữa. Nó đã trở thành một vụ đào mả. Một vụ động trời. Một vụ hi hữu mà từ xưa đến nay chưa bao giờ ở đây xử lý tới cả.

Mọi thủ tục bây giờ được chuẩn bị lại hết. Người ta trình báo vào văn phòng của đồng chí trưởng phòng. Người ta sắp xếp lại hồ sơ ngổn ngang trên mặt bàn.Người ta tăng cường thêm một xấp giấy trắng để đặc biệt ghi cung. Người ta cũng thay thế luôn cả đồng chí ngồi ở giữa bàn lúc nãy bằng một người chắc ở chức vụ cao hơn.

Cuộc thẩm vấn thiếu nữ kéo dài suốt ngày hôm đó. Nàng trả lời hết. Nàng thú nhận hết. Nàng mô tả hết. Ðến độ trong hồ sơ khai trình của nàng có cả sự việc con cóc bị một nhát cuốc chém dẹp lép trở thành một đống bầy nhầy. Người thư ký quều quào ghi chép cũng đã xài gần hết một thếp giấy đôi.

Bây giờ thì người ta biết được rằng nàng đã sinh sống bằng cái nghề đào mả từ trước đó hai năm. Bố nàng thuộc diện ngụy quyền đã bị đi an trí và bỏ xác trong trại cải tạo từ những năm của thập niên 60. Mẹ nàng bỏ đi lấy chồng khác, rồi cũng chết sau đó vài năm. Nàng còn hai em nhỏ. Nàng đã làm đủ mọi nghề để có thể nuôi cho hai em ăn học. Nhưng nghề nào cũng chỉ đủ nuôi một thân một mình nàng, trừ cái việc đi đào mả người chết lấy đồ dùng đem ra bán ở ngoài chợ trời. Nàng đã khai như thế. Và nàng tỏ ra thản nhiên khi nói lên những sự thực chết người như thế.

Thể theo lời yêu cầu của gia chủ đã có thân nhân bị đào tung mả lên, nàng bị giam giữ để cho tòa xét xử.

*

Nhưng một tháng sau đó, người ta lại thấy nàng xuất hiện ở khu vực chợ trời. Người nàng xanh rớt. Thân hình tiều tụy. Sức khỏe của nàng sút giảm hẳn đi. Nàng ngồi thu mình ở một góc vỉa hè như một con mèo ốm, trước mặt nàng loe ngoe mấy hộp sữa và vài bịch đường. Nghĩa là nàng chẳng bị tù tội gì hết. Nàng vẫn còn là một công dân của nhà nước xã Hội chủ nghĩa. Lý lịch của nàng vẫn còn trắng tinh.

Bởi vì khi đứng trước tòa, nàng đã rành mạch khẳng định:

“Xã hội của chúng ta là xã hội chủ nghĩa, chủ trương duy vật mà đả phá duy tâm. Chỉ những kẻ còn đầu óc duy tâm mới quan niệm rằng đào mả lên tức là xâm phạm đến linh hồn người chết.

Tôi sống bằng lao động của chính tôi. Tôi không ăn bám một ai. Tôi chỉ lấy đi những đồ dùng chôn dưới mả là những thứ mà xã hội bỏ đi, đã phế thải.

Hơn thế nữa, tôi lại dùng lợi tức của những thứ phê thải ấy để nuôi các em tôi ăn học, tức là bằng thứ lao động hợp pháp đó, tôi đã nuôi dưỡng được những mầm non của đất nước!

Vì thế, tôi là người hoàn toàn vô tội!”

Santa Ana, tháng 4-1981

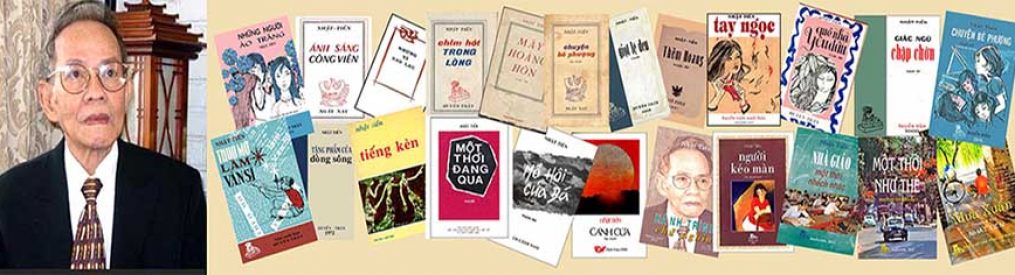

NHẬT TIẾN

Bản dịch Anh ngữ:

SHORT STORY

THE KHAKI COAT

Nhat Tien

Translated by Xuan Phong

Into this noisy crowd the young girl was elbowing her way. The stench of the rubbish heap made her feel dizzy. lt revived the nausca that had lingered in her throat since the previous day, though she had tried to drown it down with a farina candy. The sweet flavor of sugar still stuck in her teeth though the candy had completely melted away. She could speak as loudly as she liked without the fâeeling of having something entangled in her mouth.

She first greeted an old lady who was selling rolls of dry tobacco leaves displayed on a flat winnowing basket. The old lady’s reply was inaudible above the noise of the crowd. She only heard the loud voices of a few people who, standing next to her, were shouting their wares, including the obscenities of a few nearby youths. On their arms hung several pairs of Western trousers of different fabrics and colors. Most were the khaki of the bo doi (soldier). A few passers-by slopped to have a look, felt this side and that, then left without making any offer. Since the morning nobody had succeeded in selling anything, because people had had to flee whenever pubhc security men were on patrol. The whole place had a disorderly air compared with the main Dong Xuan Market nearby. The problem with the main market was that most of the displayed articles could only be sold to people with book of Stamps; there were always more sales assistants than customers. Most people withdrew from the main market to form a “fringe society”. All the members of this society were ragged and dirty; all werc jostling each other in the chaos. On rainy days thc roads became muddy.

Rubbish was scattered everywhere, making it difficulty to walk. Now and then the whole crowd would be bottled up by a bicycle with a saddle loaded with merchandisc. Curses were exchanged. Words that were forbidden at agencies, that could not be used or fully expressed to one’s heart content at conferences, were let out here without any fear of being condemned as a person who had compromised his political standing.

Youths cursed morc offen than anybody else. For some time the girl had heard this young man shouting out his vulgarities. She was not vexed at his words but his shouts were so loud that they hammered at her temples. She felt sick again. As she was aboul to takc out of her pocket another farina candy, she remembered her task. She held out the coat in her hand to a few passers-by.

The coat did attract people’s attention. It was a Western coat made out of golden- colored khaki. Its long and roomy sleeves were so skilfully sewn to the two shoulders that no wrinkles were to be seen. Down the two lapels that left bare the front part of the wearer’s chest ran two rows of three carved copper buttons on either side. The coat must have belonged to a prosperous person who a few decades ago had certainly been fashion-conscious. Because it had been well cared for it still looked quite new.

ThE girl held the coat over her head as high as she could.To a youth who was approching her, she said, “This coat fits you very well, buy it.”

He stopped, looked indifferent. Though she knew that he was merely curious, she added all the same, “Thirty dong ( piastres ), you can wear it over your sweater this winter. How warm you will be !”

The young man, who had intended to try it on, changed his mind when he heard the price. He looked at the girl with his laughing eyes. The young girl understood that it was far too expensive for him.

Another wave of customers passed and she showed them the coat, but she had lost interest in selling it. She felt sick again. She took another farina candy from her pocket and put it in her mouth. Then she discovered the cause of the nausca she had been having since the day before. lt wasn’t that she had eaten the bowl of stale wheat noodles left unfinished by her sibling the afternoon before, nor that she had caught a cold after exposing herself to the nightly frost the night before. She remembered that while using a pick she had hit a toad on its back. The animal had died immediately. She felt a chill running through her body as she thought about it. A toad, though small, is life itself. lt was she that had smashed that life and reduced it to a formless mass. That night she had wandered vaguely from one thought to another as she dug up the ealth. Now the stench rising from the pile of garbage at the edge of the market increased her nausea-she wanted to vomit.

She was on the point of leaving her place when she noticed a woman standing just in front of her. The woman gazed at the coat as if attracted by some extraordinary powerful force. Then her faced turned pale. Stretching her hand out, she look hold of the coat while she stared furiously at the girl’s face. The girl didn’t like being stared at like that. Nor did she like this woman’s pale countenance. She looked fifty but could have been younger. The girl was disturbed by the woman’s muddly eyes under her thick eyebrows.

The woman succeeded in taking the coat of the girl’s hands. The girl knew immedialely that she did not intend to buy it. She wanted to grab back the coat and run away with it but holding it firmly with her two bony hands the woman asked in an authoritative manner. “Where did you get this coat ?”

The girl felt a chill again. She was intimidated by the woman’s aggressive manner. She knew what she had to do to overcome this difficult situation. She said, “l bought it to sell it again,” then tried to snatch back the coat. Her arm was seized by the woman. She felt her skin being pinched by the woman’s sharp fingernails. She realized she had made a mistake. She should have run away when she had the opportunity. lt was too late now. The woman held her firm with her claws. ln spite of her slender body, the woman had an extraordinary strength. The girl struggled hard to break free but to no avail.

Frowning, the girl asked angrily, “Whal are you doing?”

The woman demanded, “I ask you-where did you get this coat ?”

” I bought it, to sell it again.”

“Liar! Come to public security post with me.”

The girl struggled furiously to escape. The woman held firm and started to drag her along, making a disturbance in this corner of the market. People gathered around and started asking questions :

“Is she a thief ?”

“A looting?”

” Beat her ! Doesn’t like working! Just wanted to be a parasite !”

A few ” comrades” who worked as security agents in the market were on hand within a minute. One rushed forward and helped the woman by holding the girl’s other arm. Her hair came loose, as did her vest., but she saw nothing, could distingush nothing in the melee in front of her. She thought of her two siblings at home, she thought of the woman’s furious eyes, of the yellow coat, of the crushed toad. Everything was rushing so quickly through her mind that she felt dazzled, stifled and she let herself be dragged away like an animal.

At the public security post the woman said:

“Dear comrades, my husband was buried just five days ago. I remember everything about it. I dressed him in this khaki coat before his burial. This khaki Western coat has been in our possession for a few decades. I can show you the marks on it. While I was at the market today I saw this girl trying to sell the very coat my husband was buried in. Plcase, dear comrades, find out how this coat has reappeared in this world? How does this girl come to have it?”

Everyone in the public security office was stunned. The staff at nearby desks stopped working to stare. Never before had anyone come across such a strange story. All eyes were on the girl. She looked tired after being dragged the whole way through a hostile crowd, but she had recovered some of her calmness. Her demeanor hid her emotions. She stood like someone ready to stand and fight against anything.

To the woman she said, “Yes, this coat belonged to your husband. There’s no need to shout like that.”

That was the comfirmation the woman wanted. She pointed her two hands toward the crowd of public security agents standing there as if she would have liked to say, “Well, what did I tell you? I didn’t make it up, did I ?” Then she sat down, breathing heavily. She had got what she was after; now il was up to the state. The state should settle the matter for her. If she was not satisfied, she would take it up with the municipal committee. The eagerness with which the public security agents had so far dealt with this case had given her a certain satisfaction. Her face relaxed. Then everybody in the office heard her sobbing. She used the waist band of her mourning clothes to wipe her face in a deliberate way to draw people’s attention. This immediately brought the desired result as the public security agent on duty comforted her, then turned to the girl and said, “Be reasonable, tell me everything now, unless you want to spend the rest of your life in prison until the day the stocks around your neck get rotten and eaten by woodworms.”

Glancing up, the girl retorted, ” Dear comrade, does our regime still use the stocks?”

The agent’s face paled, then turned red. He raised his voice to erase the error he had committed. “Don’t try to evade the question. Tell me, where did you find the coat?”

“Why should I evade the question?” said the girl. ” I have nothing to hide. And don’t you “thou” and “thee” me. I am one of the masses. You serve the masses. You have no right

to talk to me like that.”

Struck dumb by these two successive blows, the agent looked at the girl sitting in front of him with surprise and curiosity. Expcrience had taught him that anyone with such a fearless attitude might have a relative worthy of respect. It was best to remain calm until he knew more about her. He softened and lowered his voice, “All right, I withdraw what I said. But I warn you in advance that you have to tell me everything. Where did you get this coat?”

The girl simply said , “From the graves,” in her sharp unemotional voice.

Everybody was taken aback. Even the woman stopped sobbing, and looked with wide eyes at the girl. Of course it had been taken from a grave, but she couldn’t believe such a terrible deed had been carried out by this slender girl. She suddenly remembered what she had done half an hour before. She’d caught this girl in the middle of thc market, brought her through a long street to this public security post-and hadn’t been stabbed by her. She felt she had indeed just escaped a great calamity.

Now there was more seriousness in the atmosphere. This was not a thcft or a robbery. lt was digging up a grave. It was so rare they had never dealt with it before. Every procedure had to be reconsidered. The matter had to be brought the attention of the senior offcial. Files scattered on the desks were rearranged. A packet of white paper was brought out for the secretary to write down the defendant’s statement. The agent, who a moment earlier had sat at the desk in the middle or the room, was replaced by another man of higher rank.

The girl’s interrogation lasted all day. She answered all the questions and told the whole truth. She described everything, including the fact that a toad had been crushed and deformed by a pickaxe. The secretary, with his awkward handwriting, used up all his paper in the process.

Now it was known that she had earned her living for two years by digging up graves. Because of his connection with the puppet government, her father had been sent to a reeducation camp and there he had died. Her mother remarried, then died a few years later. She herself had two siblings to look after. She had been through a number of jobs, but only digging up graves to strip the dead had proved lucrative enough.

At the request of the woman whose husband’s grave had been dug up, the girl was detained to await trial, but one month later, she reappeared at the flea-market. She looked pale and emaciated. Her health had deteriorated.

She squatted, gathering herself together in one corner or the pavement. ln front of her were a few cans of condensed milk and some packets of sugar. Her curriculum vitae, still stainless, allowed her to assume any occupation she liked because, when brought to the Court, she had stated in these terms:

“We are now living in a socialist country. Materialism is being upheld and idealism attacked. Only those whose minds are idealislic would think that to dig up a grave is to violale

a dead person’s soul. As for me, I earn my living by my own labor. 1 do not live as a parasite, at somebody else’s expense. I have only taken what was buried in a grave, i.e. what had been discarded by society. Furthermore, I have used the profit I made to bring up my siblings, which means that by this kind of labor I’ ve reared two children who belong to the next generation and in whose hands will lie the fate of our socialist country. Therefore, I am totally innocent.”

Translated by Xuan Phong

( from CHIEC AO TAY VANG by Nhat Tien)

**********************

Bản dịch Pháp ngữ:

LE PATELOT JAUNE

(“Chiếc Áo Tây Vàng” – Nhật Tiến)

Text français de LY VAN

Dans cette foule bruyante, la jeune fille se faufila quand même. Elle fut légèremẹnt prise de vertige à cause de la puanteur qui se dégageait du monceau d’ordures situé près de là. Cette puanteur lui rappela la nausée qui n’avait cessé de la hanter depuis la veille quoi’quelle l’eût éprimée avec un bonbon de farine. Car si un peu de sucre d’une douceur suave restait encore quelque part dans les interstices des dents, le bonbon lui même était entièrement dissous. Elle pouvait élever la voix pour parler sans en être empêchée par quelque chose qui avait obstrué sa bouche. Tout d’abord, elle salua une vieille femme vendant du tabac en rouleaux, noués sous forme de gerbes, étalés sur un panier plat, posé à même le rebord du trottoir. La vieille femme répondit par des mots qu’on n’entendait pas clairement à cause du brouhaha de la foule. La jeune fille n’entendait que le vacarme de ceux qui, debout près d’elle, faisaient la réclame de leurs marchandises, et surtout les rires et les paroles grossières d’un groupe de jeunes gens se tenant près de là. lls avaient sur leurs bras des pantalons de coupe occidentale, de tissus variés, aux couleurs diverses. La couleur de kaki militaire prédominait. L’un d’entre eux, ayant déjà sur un bras trois ou quatre pantalons, en élevait un autre de l’autre main. Quelques hommes passant par là regardaient en tournant et retournant les pantalons, rien que pour voir, puis circulaient. Depuis le matin, personne n’a pu vendre une seule marchandise, quoique tous aient du s’enfuir trois ou quatre fois, car les policiers chargés du contrôle du marché faisaient plusieurs fois la ronde. Ceci se passait sur un petit terrain, sis juste derrière le marché Dông-Xuân (Hanoi). Il constituait la contradiction d’une zone déjà rentrée dans les normes depuis plusieurs années. Mais c’était justement à cause de son caractère secondaire qu’il était devenu beaucoup plus désordonné, plus complexe que le spectacle désert au coeur même du marché. A ce dernier endroit, tout était propre, tout était ordonné. Le seul inconvénient c’était que presque tout ne pouvait être acheté qu’avec des bons d’approvisionnement. D’autres articles attrayants n’étaient exposés que pour présenter au complet les gammes des produits, munis de l’étiquette: “échantillons”.

Ainsi, rien d’étonnant à ce que les vendeurs fonctionnaires fussent plus nombreux que. les clients. En somme, point n’était besoin de chasser les clients, tous se retiraient d’eux-mêmes du côté extérieur, créant ainsi une société en marge de la société. lls étaient tous aussi misérables les uns que les autres, se bousculant en désordre, au milieu des tas de fléaux, de paniers, de corbeilles éparpillés sur toutes les voies d’accès. Les jours de pluie, le chemin était recouvert d’une vase gluante produisant des flip – flap quand on y marchait. Les immondices étaient jetées pêle-mêle, on se disputait de petits espaces pour y poser les pieds. De temps en temps, un triporteur s’amenait, et toute une foule nombreuse était bloquée.

Des bordées d’injures s’échangeaient, plus bruyantes encore étaient les disputes. Toutes sortes de termes grossiers fusaient ne pouvant être jeté librement pour que la bouche pût s’en donner à coeur joie, tout ce vocabulaire refoulé trouvait ici son exutoire, sans que l’on pût s’accuser réciproquement de déviationnisme ! Il fallait compter les jeunes gens parmi ceux qui employaient le plus souvent ce langage ordurier. Depuis un long moment, la jeune fille entendait des dizaines de fois des phrases grossières sorties de la bouche du jeune homme qui se tenait le plus près d’elle. Elle ne s’offuquait pas des vocables qu’il employait, mais de sa voix tonitruante. Cette voix lui vrillait les tempes, semblable a un marteau frappant sur une enclume, avec un bruit sec et aigu. Elle recommença à éprouver la nausée. Elle voulait prendre dans sa poche un autre bonbon, quand elle se rappela sa missìon. Elle abandonna l’idée de prendre le bonbon, éleva la veste qu’elle tenait à bout de bras et invita un groupe de clients qui passaient par là. L’habit attirait l’attention de tout le monde. C’était une veste coupée à l’occidentale, en toile kaki. Elle était très vieille et usée, mais c’était pour cette raison qu’elle revêtait un aspect très européen. Les manches étaient longues et larges, ajustées aux épaules de manière très habile, sans un pli. Le col ouvert avec des revers descendant jusqu’à la poitrine, dans leur prolongement couraient deux rangées de boutons, dans chaque rangée, trois boutons en cuivre ciselé, tout cela reflétait quelque chose d’opulent et devait appartenir il y a quelque vingt ou trente ans, à un fin connaisseur. Ce paletot était bien vieux, mais comme la toile était de fabrication étrangère et qu’il avait été bien conservé, il gardait un aspect élégant. La jeune fille éleva la veste au-dessus de sa tête et dit à un homme qui venait vers elle :

– Ce paletot vous va à merveille, monsieur, prenez-le !

Le client s’arrêta, indifférent. Sachant qu’il n’était que curieux elle n’en continua pas moins de dire :

– Trente piastres ! Pour cet hiver, de le porter pardessus un vêtement en laine, comme ça tiendra chaud ?

L’homme esquissa un geste de la main vers l’habit, mais entendant le mot “trente”, la retira immédiatement. Il regarda la jeune fille en lui souriant du regard. Celle-ci comprit tout de suite que des gens comme lui ne pouvaient acheter que des nippes à bas prix valant trois piastres. Voyant un autre groupe de clients, elle refit son offre. Son accueil et son attente devenaient de moins en moins chaleureux. Elle recommença à ressentir son malaise: la sensation de nausée la serrait de nouveau à la gorge. Elle prit dans sa poche un autre bonbon qu’elle mit dans sa bouche. A présent, elle découvrit l’origine de cette nausée qui l’obsédait depuis la veille. Ce n’était pas parce qu’elle avait avalé le bol de vermicelle avarié laissé par son jeune frère l’avant veille. Ce n’était pas non plus parce qu’elle avait pris froid après s’être exposée à la brume nocturne. Elle se rappela qu’en maniant la pioche, elle avait donné, par inadvertance, un coup juste au milieu du dos d’un crapaud. La pauvre bête n’avait pas eu le temps de jeter un seul cri avant d’être complètement aplatie. après un “flop” sec de la pioche. Elle avait la sensation que ses os brisés avaient le pouvoir de transmettre ce bruit à travers le manche de la pioche jusqà ses mains calleuses et dures. Depuis cette minute, elle sentait un léger frisson la parcourir, et plus elle y songeait, plus elle avait envie de vomir. Le crapaud était une existence. Elle a écrasé cette existence pour la transformer en une masse visqueuse. Si seulement, ce n’était que le cadavre d’un crapaud mort ! En travaillant avec la pioche, elle songeait vaguement. Si ç’avait été un crapaud mort, il ne l’eût pas hantée jusqu’à ce point.

Maintenant, cette obsession subsistait et s’intensifiait à cause de la puanteur se dégageant des alentours du marché. De nouveau, elle avait la nausée, et elle aurait voulu vomir une bonne fois pour s’alléger d’un poids, quoique, depuis ce matin, elle n’eût rien dans l’estomac, sauf ces quelques bonbons de farine.

Au moment même où elle jeta la veste sur son épaule pour quitter le marché, un client s’arrêta juste en face d’elle. Ce n’était pas un homme, mais une femme. Elle avait le regard rivé sur le paletot comme par une extraordinaire force d’attraction, puis la jeune fille vit pâlir légèrement la figure de la femme. Celle-ci ouvrit sa main pour se saisir de la veste, pendant qu’elle dardait son regard courroucé qui semblait jeter des étincelles sur les yeux de la jeune fille. Celle-ci n’aimait guère à être regardée dans les yeux de cette manière. Elle n’aimait pas davantage le teint blême sur la peau bistrée du visage de celle qui était debout en face d’elle. La femme paraissait dans la cinquantaine, mais à y regarder de près, un certain air de jeunesse flottait encore sur les commissures des lèvres et sur le front, et laissait deviner qu’elle avait tout au plus quarante ans. La jeune fille cherchait à se remémorer quels rapports auraient pu exister entre elles. Mais, dans un bref instant, elle n’eut que la sensation d’être troublée par celle qui était en face d’elle, par le regard de deux yeux sombres bridés abrités sous des sourcils assez épais. Maintenant, la femme parvint à arracher la veste des mains de la leune fille. Elle déploya la veste, la souleva des deux mains. La jeune fille s’aperçut immédiatement que ce n’était pas pour l’acheter que la femme examinait la veste de la sorte. Elle voulut la ressaisir pour s’ échapper en marchant à reculons. Mais, la femme tenait l’habit solidement entre ses mains labourées de veines bleues. D’un ton autoritaire, elle demanda :

– Où est-ce que vous avez pris cette veste ?

La jeune fille eut froid dans le dos. Elle fixa sur son vis-à-vis un regard stupéfait. L’attitude violente de la femme la troubla un moment. Mais, elle savait ce qu’elle devait faire pour passer ce mauvais quart d’heure, elle répondit d’un ton calme :

– Je ne fais qu’acheter et revendre.

Tout en parlant, la jeune fille se précipita pour reprendre la veste des mains de la femme. Elle échoua complètement dans cet effort. Non seulement elle n’arriva pas à tenir la veste, mais son avant-bras fut enserré par une main de la femme. La jeune fille sentit les ongles tranchants de son adversaire s’enfoncer dans sa chair. Dès ce moment, elle se rendit compte qu’elle avait commis une erreur. D’une manière stupide, elle avait regretté de perdre la veste. C’est pourquoi, au lieu de s’enfuir, elle a foncé sur l’ennemi. Maintenant, c’était déjà trop tard. La femme s’est accrochée à elle avec ses serres acérées. Elle sentait que la femme avait accumulé dans ce corps maigre une force extraordinaire. Elle essaya, dans un soubresaut, de s’échapper, mais les ongles tranchants s’enfoncèrent plus profondément dans sa chair endolorie. Elle grimaça légèrement et dit d’une voix irritée :

– Ah ! Que faites-vous là, madame ?

– Je t’ai demandé, répliqua vertement l’autre, où tu as pris cette veste.

– Je l’ai achetée pour mon commerce.

– Fourbe ! Viens avec moi au poste de police, on verra bien si tu pourras persister dans ton imposture.

La jeune fille résistait, la femme la tirait. Ces tiraillements causaient un grand tapage dans tout un coin du marché. D’une foule vite ameutée, partit un vacarme fait de mille interrogations lancées en même temps :

– Un vol ?

– Est-ce bien un vol ?

– Une bonne râclée, à en faire ch… sa maman ? Refuser de travailler pour vivre en parasite de la société !

Ce tapage ne tarda pas à attirer l’attention des camarades policiers qui veillaient à la sécurité autour du marché. L’un d’eux se précipita pour prêter main forte à la femme, serrant solidement l’autre bras de la jeune fille. Ceile-ci était maintenant entièrement échevelée. Deux boutons de sa tunique, sur sa poitrine, furent arrachés. Cependant, la jeune fille ne voyait plus rien, ne distinguait plus rien du spectacle confus et tumultueux qui se présentait à ses yeux. Elle songeait à ses deux frères restés à la maison. Elle songeait aux yeux méchants de la femme. Elle songeait au paletot jaune et à l’image du crapaud aplati et visqueux. Tout cela vint à elle précipitamment, accapara son esprit, et elle se laissa traîner comme on traîne une bête. Au poste de police, la femme d’âge mûr fit une déclaration on ne peut plus claire et précise :

– Chers camarades, j’ai enterré mon epoux, il y a tout juste cinq jours.Toutes les attestations et formalités concernant cette inhumation, je les ai gardées ici au complet. Lors de la mise en bière de mon époux, je lui ai laissé une veste jaune. Cette veste, la voici. Elle nous était familière, à nous, membres de la famille, depuis des dizaines d’années. Je peux y indiquer des traces et des taches que je connais par coeur. Et cependant, aujourd’hui, comme j’allais au marché, j’ai vu cette demoiselle mettre en vente cette veste que j’avais ensevelie avec mon époux. Camarades, je vous prie de faire une enquête pour savoir d’où est venue cette veste. Comment cette demoiselle a pu l’avoir entre les mains ?

Tous ceux qui se trouvaient dans la salle étaient frappés de stupéfaction. Les camarades qui travaillaient autour d’une table voisine, délaissant leur travail, ouvrirent de gros yeux. Des milliers et des milliers d’affaires compliquées s’étaient passées ici, mais on n’avait jamais rien vu d’aussi ahurissant que celle-ci. Tous les regards se dirigèrent vers la jeune fille. Elle avait l’air encore fatiguée par les tiraillements, le vacarme de la foule. Mais elle parvenait à reprendre son calme habituel, ou plus exactement, il était difficile de deviner son état d’âme derrière son mutisme et l’éclat glacial de ses yeux. Elle manifestait une attftude imperturbable, sans l’ombre d’une crainte, l’attitude de quelqu’un qui était acculé à ses derniers retranchements et se tenait prêt à tout affronter. C’était justement cette attitude qui faisait que le jeune policier qui avait commencé à gronder et à menacer finissait par baisser le ton. Elle ne se laissait injurier par personne. A la femme d’âge mur, elle dit :

– Je conviens que cette veste appartenait à votre époux. Mais vous n’avez pas besoin de crier et de faire du tapage.

La femme, du reste, ne demandait guère mieux que la jeune fille reconnût cela. Elle étendit ses bras devant elle, dans la direction du groupe désordonné des nombreux policiers qui étaient dans la salle, comme pour se justiíier :

– Vous voyez, vous voyez, je n’ai calomnié personne.

Ensuite, elle s’assit sur une chaise, haletante. Après un temps d’efforts, depuis l’instant où, dans le marché, elle s’était saisi de cette audacieuse jeune fille jusqà l’instant où celle-ci a du reconnaître que la veste était sa propriété, elle a parfaitement atteint au triomphe qu’elle avait escompté. C’était maintenant l’affaire du gouvernement. Le gouvernement en décidera, selon la justice. Si c’était nécessaire, elle porterait son cas devant le Comité Révolutionnaire de la Ville. Mais elle était déjà satisfaite de la diligence des camarades policiers. Elle sentait qu’elle aurait avantage a jouer le rôle de la jemme sincère et de bon coeur, car, de toute façon, la situation était parfaitement élucidée. Pensant ainsi, elle adoucissait nettement les traits de son visage, et bientôt, tout le monde l’entendait pleurer. De sa main, elle prit un bout de son ruban de deuil pour s’essuyer le visage avec l’intention d’attirer l’attention de tous. Ce geste eut immédiatement son effet, car le policier assis devant le bureau central se mit à la consoler d’une voix douce, et, se tournant vers la ieune fille, il tempêta :

– Si tu es raisonnable, tu avoueras tout, sinon, tu pourriras en prison, la cangue au cou.

La ieune fille, levant légèrement les yeux aux éclats toujours froids, interrogea :

– Camarade, est-il vrai que notre régime use aussi et encore de la cangue ?

A cette insolente interrogation, le visage du camarade blêmit, puis, brusquement, rougit. Il prit un ton courroucé pour effacer son propos inconsidéré :

– Ne cherche pas à t’esquiver. Ce paletot, où l’as-tu pris ? Avoue-le.

– Je n’ai pas à m’esquiver. Je n’ai pas à nier. Mais, je vous prie, camarade, de bien vouloir vous dispenser de me tutoyer. Je suis du peuple. Vous êtes un serviteur du peuple. Vous n’avez pas le droit de me parler sur ce ton.

Absourdi par cette double attaque, le policier resta brusquement interdit. Il regarda, stupéfié, la jeune fille assise en face de lui, avec un air à la fois étonné et curieux. Son expérience lui avait appris que des gens si durs devaient être d’une redoutable extraction. C’est pourquoi on ne serait pas assez sot pour enfoncer des portes dont on ne sait de quel bois elles sont faites.

Le camarade policier se repnt et dit sur un ton conciliant : .

– Ca va, ça va. Je retire ma façon de vous interpeller. Mais ie tiens à vous avertir que, quelle que soit la manière d’interpeller, vous devez tout avouer. Où est-ce que vous avez pris cet habit ?

La jeune íille lâcha brutalement :

- Dans une tombe que j’ai creusée.

Son ton fut tranchant, bref, froid, calme et sans l’ombre d’une émotion. Cela ébahissait davantage tous ceux qui étaient là. La femme elle-même, qui était en train de pleurer, arrêta ses pleurs, leva les yeux pour regarder la jeune fille. Qu’une tombe ait été violée, c’etait l’évidence même. Mais que pareille abomination ait été commise par la frêle jeune fille assise en face d’elle, cela dépassait son entendement. Brusquement, elle se remémora ce qu’elle avait fait depuis une demi-heure. Se saisir de la jeune íille au milieu du marché, la trainer tout au long d’une rue pour l’amener à un poste de police. Et pourtant, pendant tout ce temps, si elle n’avait pas reçu de la jeune fille un coup de poignard, c’est que vraiment elle venait d’échapper au plus grand des dangers. Rien qu’à y penser, elle frissonnait de peur. N’eussent été autour d’elle ces policiers en uniforme jaune, elle eût pris la fuite.

Maintenant, l’atmosphère de la salle est devenue plus sévère. Ce n’était plus ici un simple cas de vol de cambriolage ou de traffic clandestin. C’était un cas de violation de sépulture. Une affaire inouïe ! Une affaire extraordinaire que jamais ce petit poste de police n’avait eu à régler. Toute la procédure devait être réaménagée. On informa le bureau du camarade chef de poste de ce qui venait de se passer. On arrangea les dossiers éparpillés pêle-mêle sur la table. On ajouta une main de papier blanc en vue d’écrire un procès-verbal. de caractere spécial. On alla jusqu’à remplacer le camarade qui tout à l’heure était assis devant le bureau central par un autre sans doute d’un grade supérieur.

L’interrogatoire auquel était soumise la jeune fille durait toute cette journée. Elle répondait à toutes les questions, elle avouait tout, à tel point que, dans sa declaration, il était également question d’un crapaud écrasé par un coup de pioche et transformé en une masse visqueuse. Le secrétaire qui gribouillait le procès-verbal a presque épuisé la main de papier à format double.

Maintenant, on savait que, depuis deux ans, la jeune fille avait gagné sa vie en exerçant la profession qui consistait à violer les tombeaux. Son père, ayant été un collaborateur du gouvernement fantoche, avait été envoyé en rééducation dans un camp de travail depuis les années soixante et y avait laisse sa peau. Sa mère avait abandonné la famille en se remariant, et était morte à son tour quelques années après. Il restait à la jeune fille deux jeunes frères. Elle a exercé tous les métiers pour les nourrir et les envoyer à l’école. Mais aucun métier ne lui permettait de gagner leur vie, à tous les trois, sauf celui qui consistait a creuser les tombeaux afin d’y prendre des objets qu’elle pouvait écouler au marché aux puces. Tels étaient ses aveux. Et elle paraissait tout à fait naturelle quand elle disait ces vérités.

Selon la demande de la partie plaignante dont le tombeau du mari avait été violé, elie fut détenue en attendant le jugement du tribunal.

Cependant, un mois plus tard, on la voyait reparaitre au marché aux puces. Elle était toute pâle et souffreteuse. Sa santé etait nettement détériorée. Elle se tenait assise, recroquevillée, à l’angle d’un trottoir, derrière quelques boîtes de lait et quelques sacs de sucre. Son casier judiciaire restait vierge, et il lui était loisible de faire le travail de son choix, légalement.

Voici sa déposition devant le tribunal :

“ Notre société est une Société Socialiste, elle préconise le matérialisme et combat le spiritualisme. Seuls les gens encore imbus de spiritualisme pensent que violer les sépultures, c’est porter atteinte à l’âme des morts. Je gagnais ma vie en travaillant de mes propres mains. Je ne vivais aux crochets de personne. Je ne faisais que prendre des objets ensevelis dans de la terre et que la société avait rejetés, éliminés. Bien plus j’ai utilisé l’argent que j’ai ainsi gagné pour élever mes frères et les envoyer à l’école, c’est-à-dire que par ce travail, j’ai cultivé des “germes pour l’avenir” de la Patrie. Pour toutes ces raisons, je suis parfaitement innocente !”

Nhât Tiên

texte français de Ly Van